The L.A. artist building a Black American portrait archive

[ad_1]

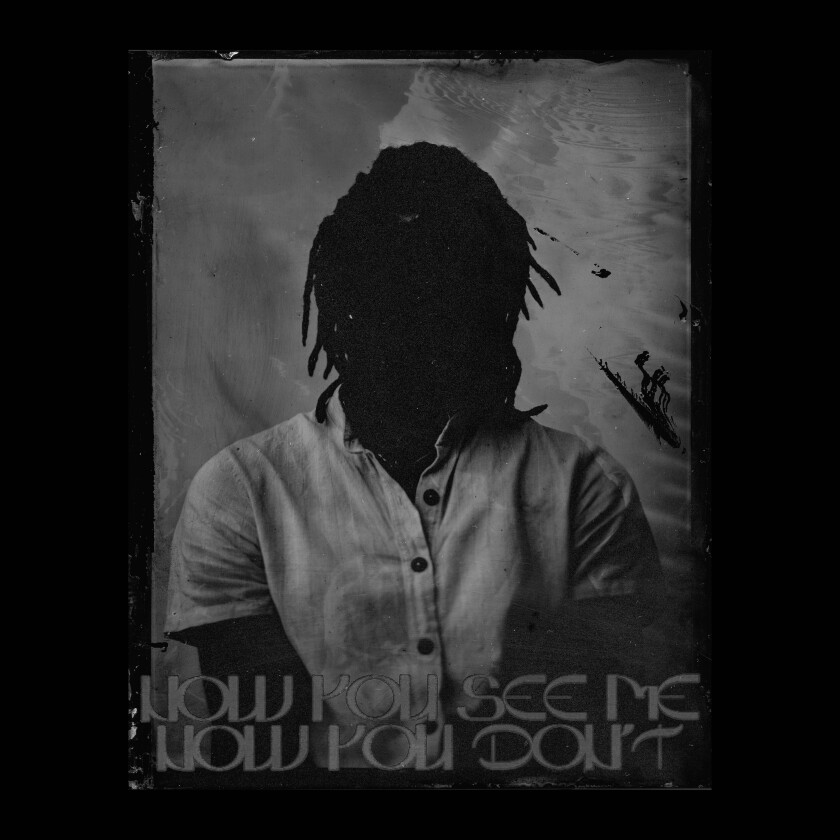

Artist Adam Davis sits for a self-portrait.

(Adam Davis)

“When people today would check with me, ‘What do you shoot?’ I utilized to say ‘everything,’” artist Adam Davis says. “But now, I just notify them: ‘Black folks. I typically photograph Black folks.’ And they get tense.”

A output coordinator for the Black-owned L.A. bookstore Reparations Club, Davis, an artist and educator, employs the bygone medium of tintype portraiture in his do the job. For his 2nd solo exhibition, “Black Magic,” Davis pinned 54 of these tintype photographs to white partitions. The portraits captured the faces of Davis’ local community, together with custom made card decks and skateboards. The weathered emulsion from the medium’s special enhancement system results in a unique vignette halo all-around Davis’ topics.

Like photographer James VanDerZee, who when chronicled the individuals of Harlem, Davis usually takes a deemed technique to documenting his contemporaries, posing individuals for portraits that celebrate their intrinsic attractiveness. “My 1st clearly show [‘People Of Paradise’] was me asking ‘Where are the Black persons?,’” he claims, “‘Black Magic’ celebrates the Black people.”

Just after displaying his portraits in November at Byrd Museum, a new artwork room in Mid-Metropolis, Davis hosted a tintype pictures workshop at Photodom, a Black-owned digicam keep in Brooklyn. Davis is now embarking on a tour of historically Black cities all over the United States, with stops in Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago and Tulsa. He will host pop-up tintype portrait periods in his pursuit to make 20,000 tintype portraits of Black Us residents — a single of the largest up to date archives of Black American portraits to day.

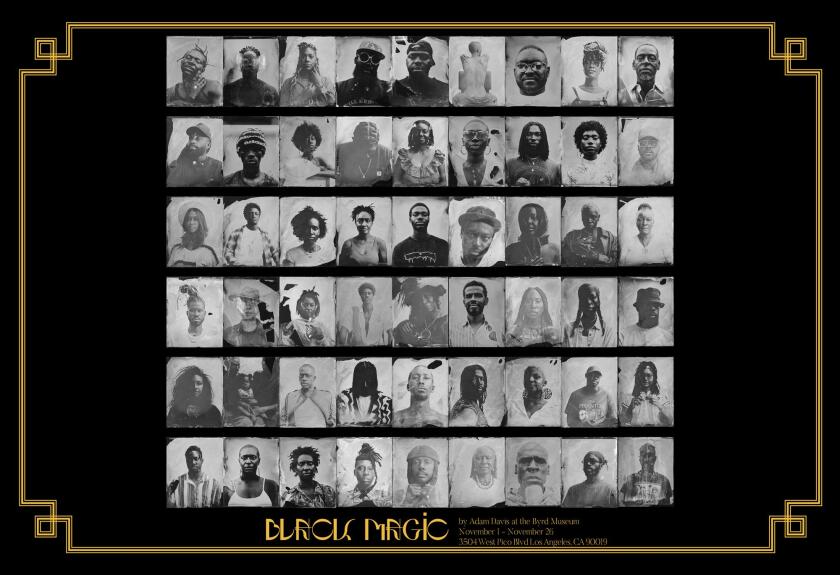

The poster for Adam Davis’s “Black Magic” present.

(Adam Davis)

In the 7 days leading up to the Byrd Museum opening, Davis meets me at the Mid-Metropolis bungalow he shares with his partner, Kai Daniels, an artist and activist. A pond babbles outside the window, and a back garden of succulents climbs up to assert the picket exterior walls. The pair moved into their house at St. Elmo Village, a 55-year-outdated Black-owned-and-operated group arts colony, just two weeks right before the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the unsure months that followed, Davis retreated to the darkroom that sits just outside the house his entrance door. The darkroom and the colony grounds ended up the eyesight of photographer and muralist Roderick Sykes, who, in 1969 at the age of 18, moved in with the mission to create a flourishing imaginative enclave within the urban sprawl. By 2020 Sykes was in the twilight of his daily life, quietly dwelling with Alzheimer’s a several cottages in excess of from Davis and Daniels. Daniels experienced developed up adjacent to the St. Elmo local community — Sykes and his spouse, artist and administrator Jacqueline Alexander-Sykes, had been a type of prolonged household for her, she states.

When Davis moved to the neighborhood, Sykes was no more time able to talk Davis says he arrived to comprehend the gravity of Sykes’ legacy as a result of the perform he left guiding — prints and sketches tucked into the darkroom’s desk drawers. “In my head I assumed, ‘when I die, this is the bar,’” Davis recalls. “If I really don’t have this quantity of work and have impacted this volume of people today…” He trails off for a minute, shaking his head lightly, “Yeah, like I’m sitting down in this guy’s biggest art piece. It is gonna make me f— cry.”

Davis, who was born in 1994, break up his time amongst his relatives dwelling on Lengthy Island and his father’s parish in Brooklyn growing up. Davis’ father, a preacher, took up pictures as a hobby, and snapped pics of Davis and their church relatives. His mom was a trainer. Davis characteristics his vocation in artwork and instruction to his early obtain to creativity.

In 2016, Davis remaining New York for Los Angeles, a new town with very little acquainted group. “I was asking yourself, ‘Where are the Black persons?’ I did not know any Black people today, I did not know anybody that seemed like me,” he remembers. Davis later on started crafting a picture sequence of Black persons keeping birds of paradise, at some point comprising his initial exhibition, “People of Paradise.”

Chrystal Brooks, bottom left, and Chrystian Brooks, top rated suitable, pose for a portrait in Adam Davis’ “People of Paradise” collection.

(Adam Davis)

For the duration of the pandemic, Davis taught himself how to build film. He grew interested in the 1820s-era technique of picture creating called damp plate collodion pictures, or tintype. He examined and executed ideas for what would turn out to be his subsequent exhibition — inviting mates and local community users above to the complex to seize their portraits on tintype. Ultimately, 100 individuals would stop up sitting down for portraits.

The darkroom developed into a sanctuary for Davis, significantly during the upheaval of COVID-19. For the duration of the pandemic, Davis dropped several liked types. “That area means a large amount,” he suggests of the darkroom. “I would go in there and just peak despair, peak suicidal feelings, like screaming top rated of my lungs and no one could hear me. I could just go in there and disappear,” he says.

While processing their grief, Davis and Daniels resolved to decamp to Oaxaca, Mexico, in December 2020. Locked down in Oaxaca, Daniels practically attended her masters classes at the Southern California Institute of Architecture. She took a study course by Kahlil Joseph centered all over the principle of Black city ownership and what that can look like from an architectural and anthropological standpoint. “You can’t converse about artwork and tradition in Los Angeles with no mentioning Kahlil Joseph,” Davis describes. “He taught [the class] how to make my favored piece of artwork [BLKNWS, a video installation] and I was like, ‘Babe, I got to know how he does this.’” Daniels started forwarding Davis recordings of her class classes.

When Davis returned to Los Angeles, he seemed at the tintype portraits he experienced taken throughout the pandemic with a renewed curiosity. Davis commenced imagining a long run earth, a single in which the tintypes resembled “futuristic ID cards.” He picked 54 portraits: the quantity of cards in a deck (jokers bundled). In the exhibition catalog of “Black Magic,” Davis writes: “What was when just an exercising in curiosity and discipline, blossomed into this extraordinary celebration of all the people and sites I hold pricey.”

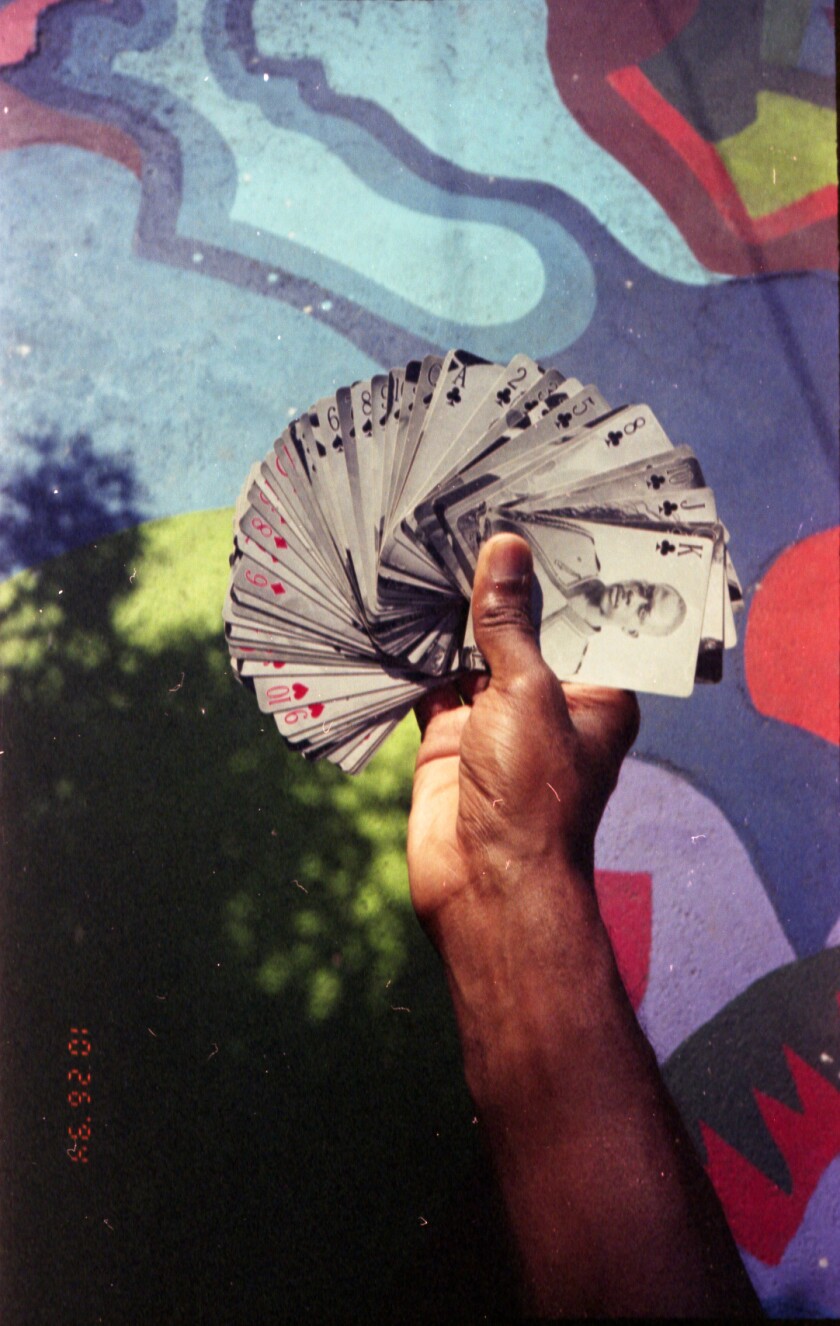

A card deck produced by Adam Davis for his “Black Magic” display.

(Adam Davis)

In tandem with the exhibition and the reserve, he developed a sequence of promotional movies, spending homage to Joseph’s signature two-channel video clip structure. “Some of the prompts from the class had been just about imagining the long run and documenting movement — capturing places by Blackness,” he claims. “It truly forced my contemplating outside the house of the box I’ve been in. I put myself in the footwear of someone who helps make movies.”

In April 2021, Sykes succumbed to his many years-long battle with Alzheimer’s. Davis channeled Sykes’ solve as he established out to discover a location for his eyesight, recalling how Sykes after described his approach to artwork-making: “Don’t wait for validation from them and they… This is what you can do with what you have, today is the best day. Yesterday’s gone and tomorrow ain’t obtained here yet.”

When programs to show “Black Magic” at a dream room fell by means of, Davis contacted Brittany Byrd, a young artist, stylist, influencer and the proprietor of Byrd Museum. Byrd is a modern graduate of Parsons and, like Davis, experienced knowledgeable setbacks in excess of the several years while pursuing her artistic vision. “When I was told, ‘You’re not Black sufficient to do the items you want to do in art,’ that’s when I stopped searching for validation,” she states. When Davis approached her with the deck for “Black Magic,” she realized his do the job felt ideal for the space.

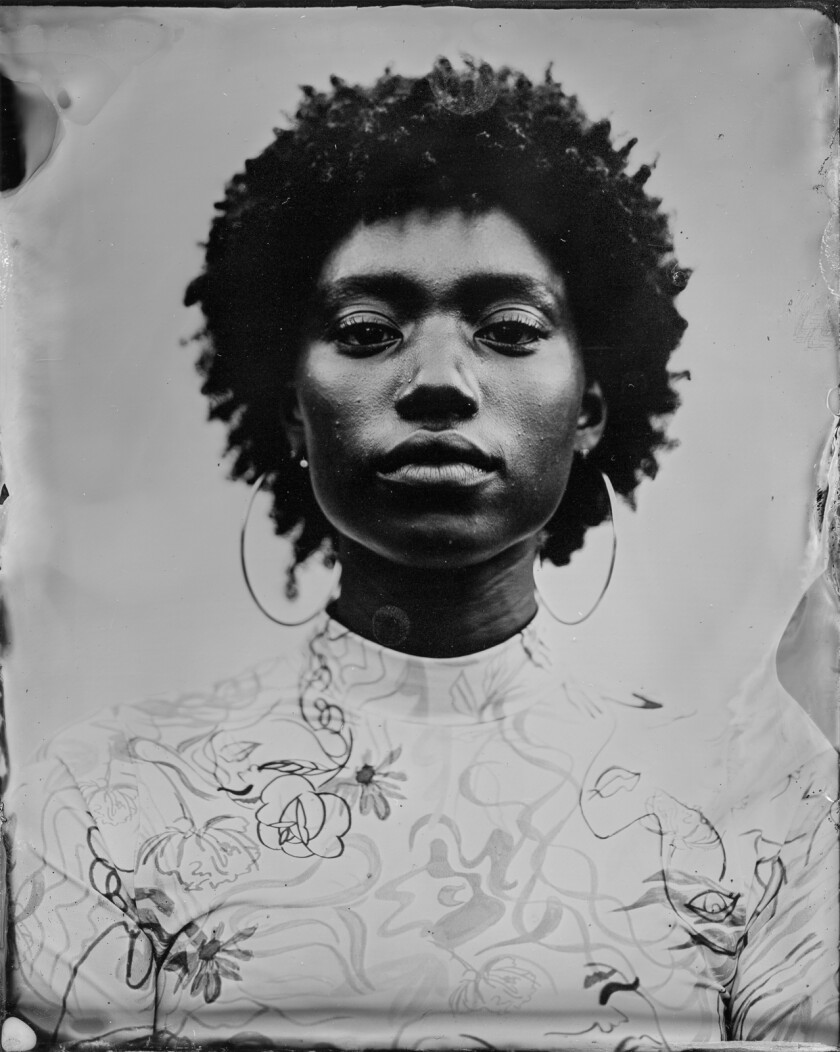

Sydney N. Sweeney poses for a tintype portrait by Adam Davis.

(Adam Davis)

With “Black Magic,” Davis imagines a long run which centers and celebrates Black people and tradition. To do so, he says, he experienced to unravel his individual activities and critique locations he perceives as regressive inside the neighborhood. “You cannot mention Afrofuturism without having chatting about queerness,” he explains. Davis started contemplating his own connection to queerness while generating the portraits for “Black Magic” and also recognized a majority of his subjects in the series determined as LGBTQ. “It’d be a disservice [not to talk about it] and realistically it’d be a lie.”

This spring, Davis will spend two months in each town he visits on his tintype tour. “It’s not a pop-up,” he states. “It’s a demonstrate up and cling out.” Davis will make two portraits of each and every human being who sits for a portrait, trying to keep one particular for his archive (and potential exhibition) and offering the other to the topic “an artifact of their existence,” he calls it.

Davis hopes to full 500 portraits on this tour, which will put a dent in his bold 20,000 portrait pursuit. “If you show up and you are Black,” he suggests. “you get a portrait.”

[ad_2]

Supply backlink