The religious works of Andrea Mantegna – my daily art display

[ad_1]

The artist I am featuring today is the fifteenth century painter, Andrea Mantegna, who created many magnificent religious works. Andrea Mantegna was born into a lower working-class family in late 1490 or early 1491 in Isola di Carturo a small village close to Padua which was then within the Republic of Venice. His father, Biagio, was a carpenter. When he was eleven years of age he started an apprenticeship with Francesco Squarcione, an Italian painter from Padua. His school was very popular at the time and over a hundred painters passed through the school. Padua, then, was looked upon as a great place to be if you were and aspiring artist and the likes of Uccello, Lippi and Donatello spent time in the city. Mantegna, who was gifted with a precocious talent, stayed with his tutor for six years.

Although he gained a great reputation as an artist and was admired by many, he left Padua and spent most of his life in Verona, Mantua and Rome where he carried on with his paintings. In 1460 he entered the service of Ludovico Il Gonzaga the Marquis of Mantua as his court artist. This engagement earned Mantegna a great deal of money which was a sign of the high regard in which his work was held. Whilst employed by Gonzaga he completed many fresco paintings of the Gonzaga family.

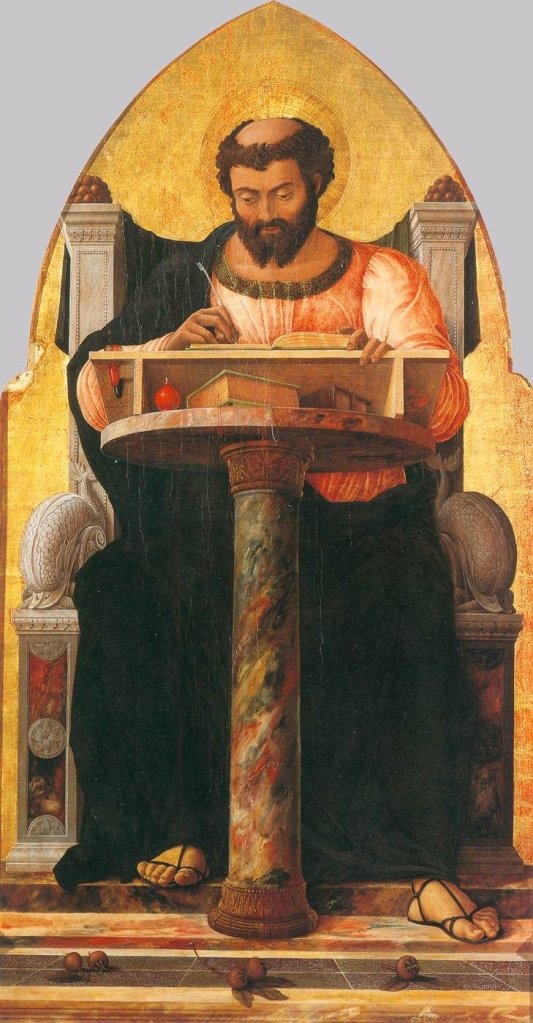

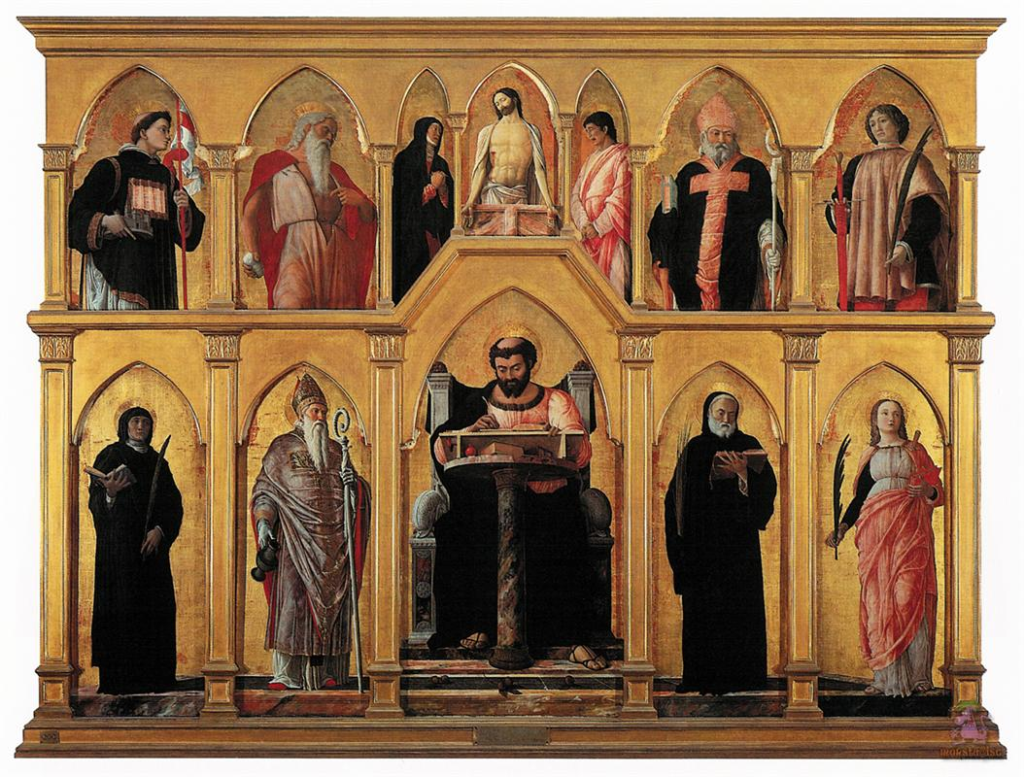

One of his early works was the St Luke polyptych which he completed as the altarpiece for a Benedictine Abbey of Santa Giustina in Padua.

Santa Giustina (St. Justina) is depicted at the lower level of the altarpiece at the far right. She is identified by the palm branch (a symbol of martyrdom) and the short sword in her breast which refers to her martyrdom in Padua in AD 303, during the persecutions of the Christians by the Roman Emperor Maximian.

In the central panel of the polyptych we see St. Luke depicted writing his gospel. Although many depictions of the saint feature an ox or calf, they are absent but in keeping faith with the fact this is an altarpiece for a Benedictine abbey, Mantegna has provided Luke him with a monk’s tonsure.

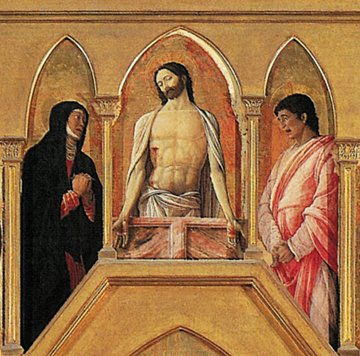

Above St. Luke, we see two saints either side of an image of the Man of Sorrows. This is an iconic religious image that shows Christ, usually naked above the waist, with the wounds of his Passion prominently displayed on his hands and side.

The panel to the far right of that portrays St. Julian the Hospitaller, a Roman Catholic saint, depicted as a young nobleman. As in many depictions of this saint, he is holding a wrapped sword, held downward. In his left hand he holds a palm branch symbolising martyrdom.

To the left of St. Luke there is a portrait of St. Prosdocimus. In one hand he holds the bishop’s crosier, which is an ecclesiastical ornament which is conferred on bishops at their consecration.

Other members of the deity depicted in the altarpiece are St. Jerome whose left hand points to his breast and his right holds a stone, which refers to the penances he endured to rid himself of shocking thoughts. We see him depicted in his usual red robes. Two other figures in the lower tier are dressed in the brown Benedictine monk’s habits, each hold the martyrdom symbol of a palm branch.

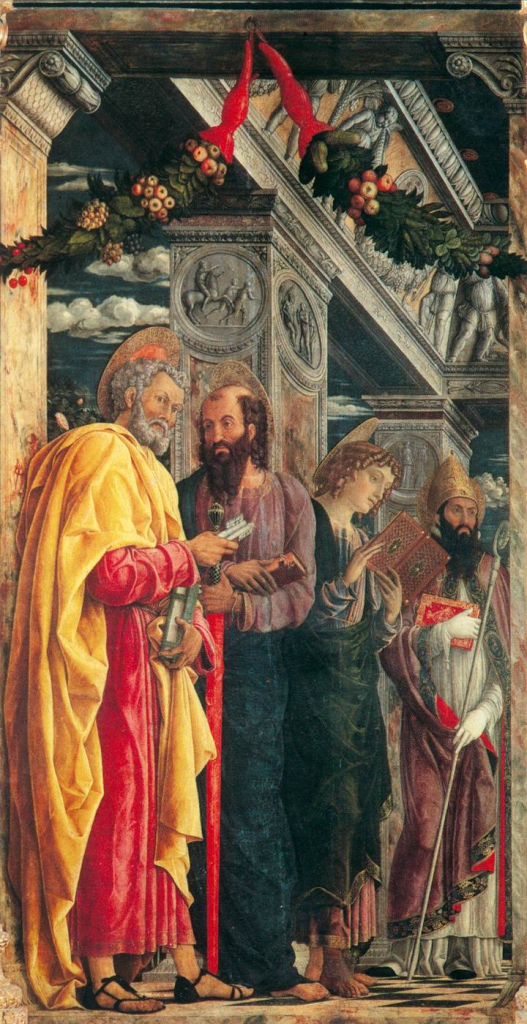

Another beautiful altarpiece fashioned by Mantegna was a commission he received from the abbot of the Basilica of San Zeno, Gregorio Correr.

It comprises of three main painting above a predella comprising of three almost square scenes. The central panel of the San Zeno Altarpiece depicts the Madonna holding her Child and surrounded by music-making angels. She is seated on a marble throne decorated with Roman-inspired reliefs. Hanging across the top of the three main paintings are garlands that appear to be affixed to the top of them.

To the left and right of this main panel there are portraits of eight saints. The saints to be included in these two paintings was the choice of the commissioning abbot. On the left are Peter, Paul, John the Evangelist and Zeno; on the right, Benedict, Lawrence, Gregory and John the Baptist.

The three paintings of the predella depict biblical scenes. Presently, the three paintings on the predella are not the originals which were taken by Napoleon in 1797 along with the main picture which was restored to Verona in 1815. The original outer two predella paintings are now in Tours, Musée des Beaux-Arts and the centre one is in the Louvre.

The left-hand panel depicts the Agony in the Garden. The setting is Gethsemane and we see an angel floating high above with the cup that symbolizes the inexorable fate reserved for Christ. Beyond the dead tree Mantegna has attempt to depict Jerusalem in accurate detail. A winding road leads through a rural scene with unrepaired boundary walls to the main gate. The central temple towering over the rest of the buildings was modelled on the Omar Mosque, which in the Middle Ages was often taken for Solomon’s Temple.

The middle painting depicts the Crucifixion. The setting is a cracked rocky plateau on Golgotha. The place of execution is marked by holes in the rock, that had already been used for other crosses. At the foot of Christ’s cross lies the skull of Adam, the first man. According to legend, Adam’s grave was at Calvary and was exposed by the earthquake when Christ died.

The panel on the right of the predella depicts the Resurrection. In the centre of this painting, the bright apparition of Christ stands out, emphasized by the darkness of the rocky grotto. The faces of the guards show a range of reactions to the miracle of the Resurrection, from a still sleepy figure gazing in front of him to a soldier rising to his feet in amazement.

The Adoration of the Magi known as the Triptych of the Uffizi, is a tempera painting on wood by Andrea Mantegna, completed around 1460 and is now part of the Uffizi collection in Florence. One of the questions regarding this triptych is whether it is one! The work is composed of three panels which only came together in 1827. The fact that they then became encased in a nineteenth century ornate frame does not make them part of a triptych and some art historians doubt that Mantegna created them as a triptych or envisaged them to be set up as one in the way they are now arranged. The three works were commissioned in the for Ludovico III Gonzaga’s private chapel in the Castle of St. George in Mantua.

The left hand panel of the triptych, known as the Ascension panel, we see a number of saints, gazing upwards at Christ as he floats skywards surrounded by a mandorla of angels. Immediately below Christ stands Mary, who faces towards us in the lower section of the panting, slightly raised on a ledge of rock.

The central panel of the triptych is the Adoration of the Magi. The three Magi symbolize both the three ages of man and also the three continents which were known at that time, Asia, Europe, and Africa. The adherents of different cultures among the followers of the kings are depicted realistically – they were familiar because of the activities of cosmopolitan Venice, a major trading centre and slave market. Once again we see the mandorla of angels around the Virgin Mary. Mandorla is an Italian word for almonds or almond shaped. It is a term often used in Christian art when describing an aureole enclosing figures such as Jesus Christ or the Virgin Mary

The panel on the right depicts the Circumcision of Christ on New Year’s Day, eight days after he was born as was written in the bible (Luke 2:21-24):

“… On the eighth day, when it was time to circumcise the child, he was named Jesus, the name the angel had given him before he was conceived. When the time came for the purification rites required by the Law of Moses, Joseph and Mary took him to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord (as it is written in the Law of the Lord, “Every firstborn male is to be consecrated to the Lord and to offer a sacrifice in keeping with what is said in the Law of the Lord: “a pair of doves or two young pigeons…”

On the left of the painting we see Joseph carrying a wicker basket, in which are two pigeons.

Mantegna moved with his family to Mantua at the behest of the Marquis Ludovico III Gonzaga of Mantua. On many occasions Ludovico had tried to persuade the artist to enter his service. Finally in 1460 Mantegna was appointed court artist where his salary was seventy-five lire a month, a very large sum of money in those days. Mantegna was the first painter of any repute to be based in Mantua. During Mantegna’s long stay in Mantua, he and his family lived near the San Sebastiano church dedicated to St. Sebastian. Maybe this is what fascinated Mantegna with the saint as he went on to paint three versions of Saint Sebastian.

It has been suggested that the first painting by Mantegna depicting Saint Sebastian was completed around 1459 whilst he was still living in Padua. A few years earlier many of the Padua citizens had been taken ill, many of whom died. Mantegna contracted the plague virus but he managed to recover from the deadly disease. Saint Sebastian received the widest veneration and was called especially in times of plague as an emergency helper. It is thought that the portrait of the saint was commissioned by the Padua city elders to celebrate the end of the pestilence outbreak. Mantegna completed the work in 1459, a year before he left the city for Mantua.. Sebastian is tied to the ruins of a Corinthian column, his body is pierced with numerous arrows.

Look at large white cloud at the top left of the painting. You should just be able to make out the figure of a man astride a horse. According to the Italian art historian Battisti, the theme refers to the Book of Revelation (19: 6-11):

“…Then I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse! The one sitting on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war…”

The nude figure of the martyr, which resembles a stone sculpture, is placed in front of an antique architectural backdrop, which looks even more “authentic” due to the Greek signature (“the work of Andrea”) on the left edge of the pillar. This first version of Saint Sebastian can be found in the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna.

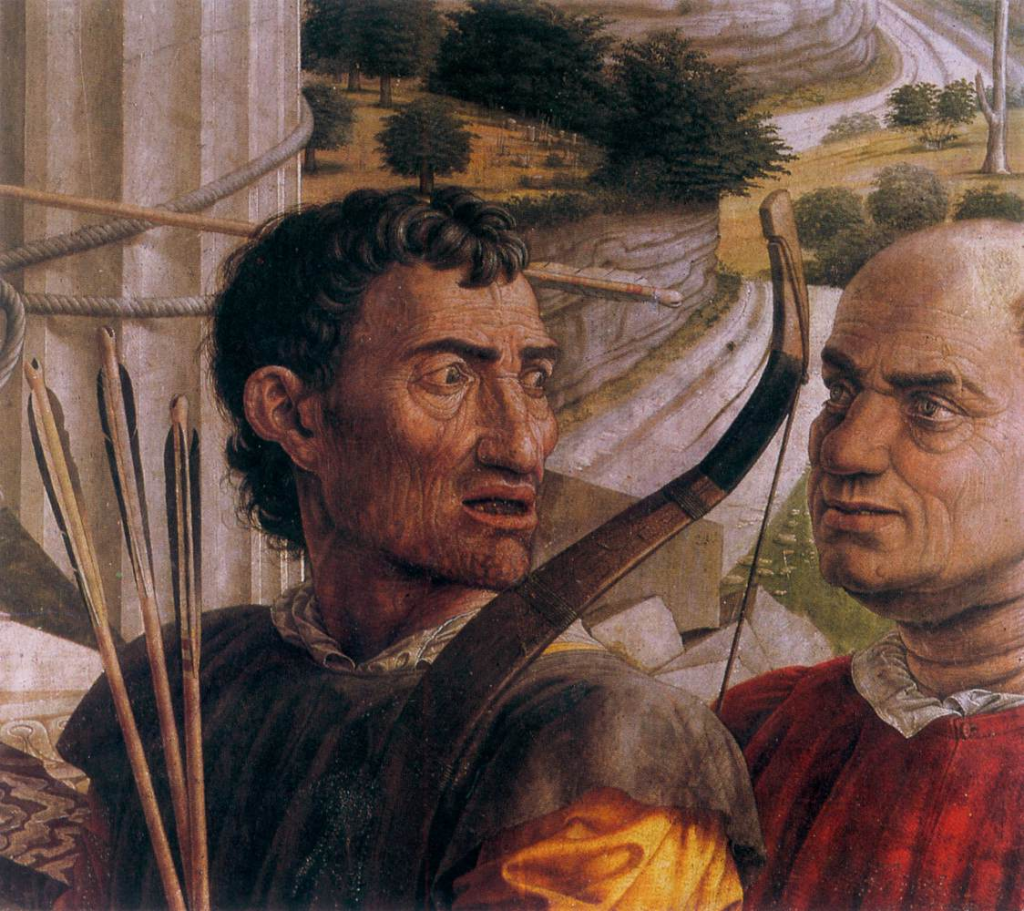

Mantegna’s second version of his depiction of Saint Sebastian, which he completed around 1480, is now part of the Louvre collection in Paris. The Louvre’s St. Sebastian was once part of the Altar of San Zeno in Verona. In the late 17th century-early 18th century it was recorded as being in the Sainte Chapelle of Aigueperse, in the Auvergne region of France. Its presence there is related to the marriage of Clara Gonzaga on February 24th 1482, in Mantua, at the age of seventeen, to Gilbert of Bourbon-Montpensier, who in 1486 succeeded his father as Count of Montpensier and Dauphin of Auvergne. It remained there for over four hundred years until it was acquired by the Louvre in 1910 part of the art and ancient book collector, Jules Maurice Audéoud’s legacy to the State.

The picture depicts the saint with a well sculpted body, tied to the ruins of a Corinthian column and pierced by numerous arrows. We look at him from below which enhances our perception of the strength and power of his figure. Sebastian’s head and eyes are turned toward Heaven which is affirmation of his unwavering Christian beliefs whilst bearing the pain of martyrdom. At his feet are a pair of grim-faced archers. Their inclusion is intended to create a contrast between the man of steadfast faith, and those who are only attracted by disrespectful and evil pleasures. It is thought that the man with the arrows is Mantegna himself.

Look at the detail Mantegna has put into the background. The classical ruins are typical of Mantegna’s pictures. The cliff path, the gravel and the caves are references to the complications of trying to reach the Celestial Jerusalem, the fortified city depicted on the top of the mountain, at the right middle-ground of the painting, and described in Chapter 21 of John’s Book of Revelation:

“…Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband…”

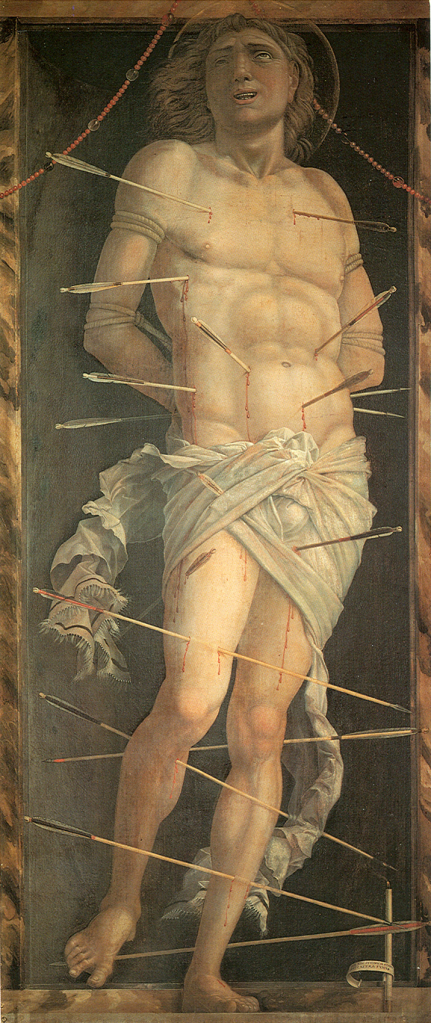

Andrea Mantegna’s panel depicting Saint Sebastian, now in the Galleria Franchetti at the Ca’ d’Oro, is the last of his three paintings of Saint Sebastian. This painting, like the previous two, focuses on Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom, in which he is executed by a firing squad of archers who plunged their arrows into his body. Given that these arrows inflicted numerous wounds all over his body, Sebastian came to be invoked during times of the plague, due to the many body sores that it provoked. The story goes that Sebastian miraculously survived the execution due to the strength of his faith. He, according to legend, was rescued and healed by Saint Irene of Rome, who also became a popular subject for 17th-century artists. Shortly after his recovery he went to Emperor Diocletian to warn him about the fate of sinners, and as a result was clubbed to death.

Whereas the first two of Mantegna’s depictions of Saint Sebastian resemble each other in style and represent the saint in a setting of classical architectural ruins, with lush landscapes and blue sky filling the background, this third is more sombre and is in complete contrast with the Montagne’s earlier works featuring the martyred saint. In this version he is silhouetted against a neutral, shallow background, brown in colour. Look at the facial expression in this version. It makes viewers much more aware of the pain he is suffering.

In the lower right corner, an inscription wrapped around a smoking extinguished candle reads

“…NIHIL NISI DIVINUM STABILE EST. CAETERA FUMUS…”

(Nothing is stable except the divine. The rest is smoke.)

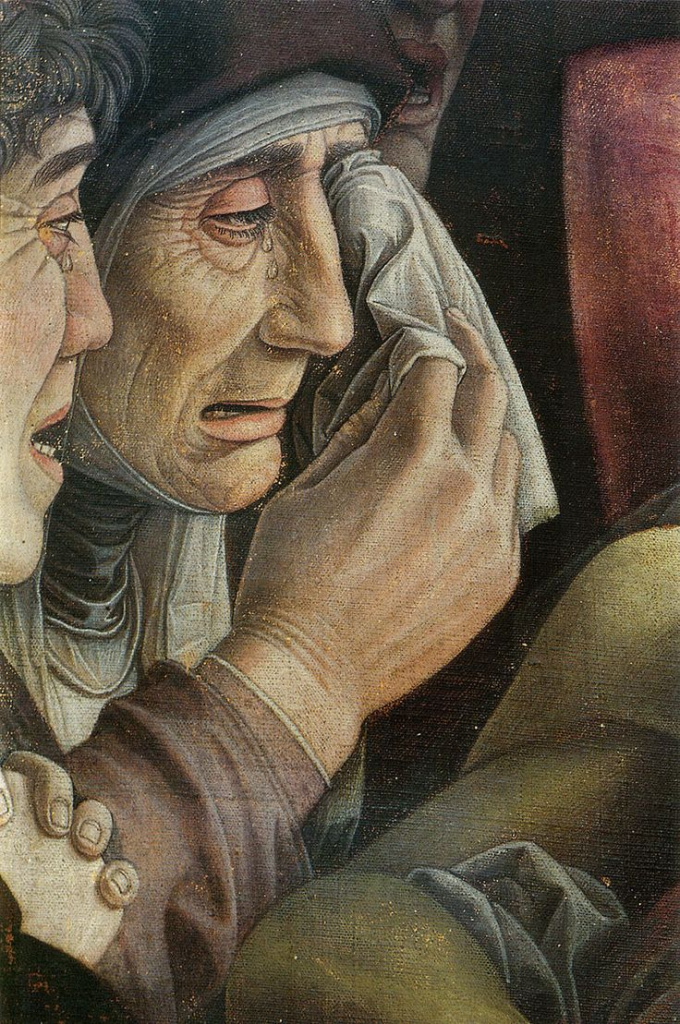

I cannot finish this blog about Mantegna without focusing on my favourite work of his, The Lamentation of the Dead Christ which was completed around 1490. It is one of very few oil on canvas paintings of the period. It is an almost monochromatic vision of Christ. The painting has a limited amount of tonal colouring, mainly pink, grey and golden-brown. The setting of the painting seems to be a morgue-like and claustrophobic space with its cold dark walls. This poorly lit space intensifies the paleness of the body. The forceful image is of the body of Christ laid out on a stark and granulated marble slab. Mantegna has toyed with the rules of perspective making the head large, whereas if the rules of perspective had been adhered to then the head would be much smaller than the feet. There is an intense foreshortening of the body which makes it appear heavy and enlarged.

Christ’s suffering, before death, is plain to see. Mantegna has given us an unusual vantage point. It places the observer at the feet of the subject and by doing so, adds to one’s sense of empathy. It could almost be described as a gruesome sight. The face of Christ is lined. His head of wavy hair rests upon a pink satin pillow. The wounds seen on the back of his hands are like torn paper, as is the horizontal cut in his side made by the spear. It is almost blasphemous, as here Christ has not risen from the dead and he is like us mortals. In the foreground are the feet of Christ each with dried puncture marks made by the crucifixion nails. Look at the skill in which Mantegna has painted the folds of the shroud.

At the left we have three mourners, Mary, Saint John and perhaps slightly hidden by the other two mourners, Mary Magdalene. Their tear-stained faces are distorted in grief. These contorted facial features derive from the masks of classical tragedy. One cannot help but be moved by their expressions.

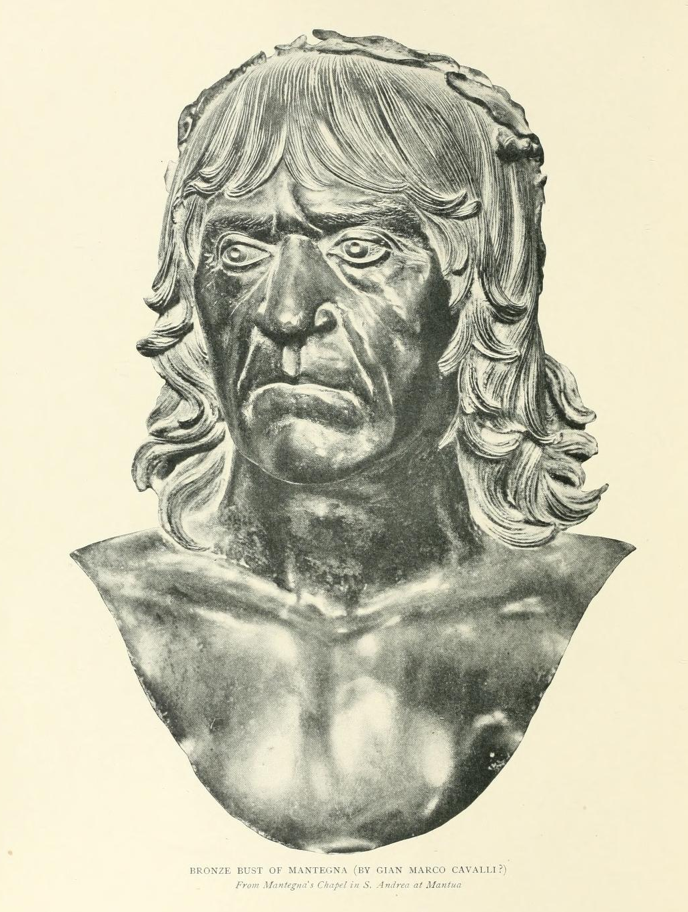

In terms of Classical art, Andrea Mantegna was one of the greatest of his time.

[ad_2]

Source link